Jalopy Jottings

Wednesday, March 25, 2020

Genevieve. (1953 film)

Coronavirus notwithstanding, it's still too cold in my garage to work on the Model T and get a couple of fresh tyres on the wheels, ready for the forthcoming driving season.

That's how I found myself watching this classic British film from 1953.

Set against the background of the London to Brighton veteran car run, it is centered around the friendship, (and rivalry) between two friends Alan McKim, (owner of the eponymous 1904 Darracq) played by John Gregson, and Ambrose Claverhouse portrayed by Kenneth More who drives a 1905 Spyker. Along with their long suffering wives and girlfriends played by the stunning Dinah Sheridan and Kay Kendall respectively.

The run goes well for Claverhouse, but not so well for McKim, and as a result the married couple end up spending a night in a rather terrible hotel. This part of the film features a truly hilarious performance from Joyce Grenfell as the hotel receptionist.

After a fractious evening at the post event party, fuelled by alcohol and petty jealousies. McKim and Claverhouse decide to race back to London from Brighton the following day, for the princely sum of one hundred pounds, (which was earlier established be nearly all the McKim's savings). The women being unwitting partners in this highly illegal event.

It is from here on that the film really gathers its comedic steam with farcical situations piled one on top of the other with such frequency it's difficult to keep track of them. Suffice to say that the film reaches a happy ending in its own bizarre way.

It can be difficult to judge a film that is 67 years old. As attitudes, like the times have changed. For instance, though the couples "kiss" you never see their lips touch. Likewise, any amorous activities are shunned. Which does lead to a very amusing double entendre as the film fades from the McKim's bedroom to the to the start of the car run and the commentators voice over could cleverly be taken both ways...

It's not a riotous, laugh out loud comedy. It's driven by the characters and the situations they find themselves in, from the pig headed pride of Alan McKim, to Ambrose Claverhouse's male chauvinism. A man who thinks nothing of telling his girlfriend (Kendall) to "put her back into it" as she stands calf deep in water trying to push the Spyker out of a ford. As the men battle with each other in their boorish way, the women are content to get along and many times put their partners in their place with a wry glance or a put down remark.

Why should you watch an almost 70 year old film? For a start, it is one of the great films of the twentieth century. A film that is the equal of any British comedy from the great Ealing Studios. Then there's the soundtrack, performed by harmonica virtuoso Larry Alder that perfectly complements the feel. It's a film that portrays a way of life now gone, post war Britain where politeness and good manners worked wonders and an honest sounding "I'm sorry officer" would get you let off a speeding ticket.

I can't finish though, without mentioning one scene about 10 minutes from the end that defines this as the ultimate classic car film. As the two cars chase into London, they are stopped by a policeman directing traffic. An old gentleman, played superbly by Arthur Wontner, comes out of a shop, spies the car, and begins to wax lyrical on how he met and courted his wife in a Darracq like Genevieve. Listening to this old man recount his story as Claverhouse speeds away in the Spyker, McKim is sure to loose the race, the bet, and the car. But it doesn't matter and his face softens as the story lengthens, and in the end he offers to take the old man and his wife for a ride in Genevieve the next day. This is when you realise that this film really "gets" what it means to own a classic car of any vintage. I'm sure we've all come across person looking at one of our cars and has been regailed with tales of how they, or a friend had one. It's always a special moment for me when that happens and this film realises that like no other film had done before, and probably ever will. That is why you should watch it.

Sunday, December 8, 2019

Matters arising

You may remember, a month ago I introduced you to Thomas Hyler-White and his project cars for the English Mechanic magazine. In the intervening time, a couple of things have come to light to add a bit more to the story.

Firstly, I said that only two models of the first project car survived. The one in a Bonhams auction that started my quest for more information, and another unknown one.

Well, I am happy to report that the unknown one is now known. I found a picture on an Australian car enthusiast's Flickr page. It was built in 1999 using an original crankshaft and flywheel. Everything else was made by hand, including the crankcase.

The Veteran Car club, THE authority on veteran and vintage cars around the world, have certified it as a 1902. Because even though the age of the contemporary parts and the original construction articles were faithfully followed, there were several improvements to the original design detailed in the letters pages of the EM that this new construction has incorporated. The car currently resides in the McFeeters Car Museum, in Forbes, NSW, Australia, and makes regular visits to car shows. You can find another picture of the car on the museums Facebook page.

The second thing I discovered comes from the pages of the American Magazine, "The Horseless Age".

I have remarked in earlier posts, that there seems to have been an informal link between the two magazines in that they would share articles, photographs, and drawings.

The drawings of Hyler White projects were one of the things shared between the two publications. However in the editorial introduction to this project they were non too complimentary in what they had to say.

"It might appear from the wording of the articles that the vehicle is intended to be built by amateurs and others from the drawings with which the article are illustrated. We do not believe that efficient vehicles of this class can be built by amateurs”.

Which is a bit of a surprise when you look through the pages of The English Mechanic magazine and see all the glowing reports on projects built to, or inspired by, Hyler-Whites articles.

As the Horseless Age is a trade magazine, and this is still the early days of the automobile. The proprietors of the magazine have no idea if the automobile was here to stay or not, or if even the mass produced automobile would play second fiddle to home built personal projects. Maybe they were just protecting their interests, putting you off building your own car.

They go on to suggest that the engine probably lacks power, and that the transmission is less than effective for American uses. Even though in Europe vehicles of this kind have competed thousands of miles, as they freely acknowledge. So they really don't appear to be in favour of this undertaking. They invite criticisms from their readers and close the editorial by almost apologetically telling their audience that the series of articles may take some time to finish.

But the story of the construction of the second English Mechanic car gives me hope. Perhaps somewhere in an old barn here on the Minnesota Prairie, is an early 1900's 4hp engine sitting unloved and ignored. I could find it, restore it and bring it back to life. Then build a car around it using the plans and articles in the magazine. To begin such a project next year, the centenary of the passing of Thomas Hyler-White the designer, You have to admit there's a certain air of nostalgic romanticism there.

It almost certainly won't happen and I'll end up using my model making skills to build a scale model of the car instead. But we can all dream can't we?

Firstly, I said that only two models of the first project car survived. The one in a Bonhams auction that started my quest for more information, and another unknown one.

Well, I am happy to report that the unknown one is now known. I found a picture on an Australian car enthusiast's Flickr page. It was built in 1999 using an original crankshaft and flywheel. Everything else was made by hand, including the crankcase.

The Veteran Car club, THE authority on veteran and vintage cars around the world, have certified it as a 1902. Because even though the age of the contemporary parts and the original construction articles were faithfully followed, there were several improvements to the original design detailed in the letters pages of the EM that this new construction has incorporated. The car currently resides in the McFeeters Car Museum, in Forbes, NSW, Australia, and makes regular visits to car shows. You can find another picture of the car on the museums Facebook page.

|

| English Mechanic No.2 (image courtesy of Classic Cars Australia) |

I have remarked in earlier posts, that there seems to have been an informal link between the two magazines in that they would share articles, photographs, and drawings.

The drawings of Hyler White projects were one of the things shared between the two publications. However in the editorial introduction to this project they were non too complimentary in what they had to say.

"It might appear from the wording of the articles that the vehicle is intended to be built by amateurs and others from the drawings with which the article are illustrated. We do not believe that efficient vehicles of this class can be built by amateurs”.

Which is a bit of a surprise when you look through the pages of The English Mechanic magazine and see all the glowing reports on projects built to, or inspired by, Hyler-Whites articles.

As the Horseless Age is a trade magazine, and this is still the early days of the automobile. The proprietors of the magazine have no idea if the automobile was here to stay or not, or if even the mass produced automobile would play second fiddle to home built personal projects. Maybe they were just protecting their interests, putting you off building your own car.

They go on to suggest that the engine probably lacks power, and that the transmission is less than effective for American uses. Even though in Europe vehicles of this kind have competed thousands of miles, as they freely acknowledge. So they really don't appear to be in favour of this undertaking. They invite criticisms from their readers and close the editorial by almost apologetically telling their audience that the series of articles may take some time to finish.

But the story of the construction of the second English Mechanic car gives me hope. Perhaps somewhere in an old barn here on the Minnesota Prairie, is an early 1900's 4hp engine sitting unloved and ignored. I could find it, restore it and bring it back to life. Then build a car around it using the plans and articles in the magazine. To begin such a project next year, the centenary of the passing of Thomas Hyler-White the designer, You have to admit there's a certain air of nostalgic romanticism there.

It almost certainly won't happen and I'll end up using my model making skills to build a scale model of the car instead. But we can all dream can't we?

Sunday, December 1, 2019

The History of the Doctors Coupe

|

| My 1926 Doctors Coupe |

There's many a Model T Ford owner who will swear that the Doctors Coupe is a type of Model T, that it was a specific type of T made specially for physicians. There are just as many that will say that there’s no such thing as a Doctors Coupe and it's just a clever piece of marketing. On the Model T forums on the internet it’s one of those “hot button” topics along with “what motor oil should I use?” and “what’s the best material for transmission bands?”.

I have even seen one person state with the greatest authority that the term Doctors Coupe was coined by Cadillac in 1906, with their first enclosed car, the model M. At the end of this post I shall present evidence to the contrary.

What exactly is a coupe? The word coupé comes from the French verb to cut, “couper”. (KOO-PAY is the correct pronunciation. KOOP being an Americanization)

This new type of carriage appeared a the end of the 17th Century. It was created by cutting off the front of a Berlin or (Berline) coach, thus removing the rear facing seats. This created a small, lightweight private coach, suitable for when the women of the time wanted to go out shopping. It was known as the Berline-coupé. Which quickly was shortened to coupé.

Where Doctors came into it, I do not know. Doctors are recorded using coupes in the days of the horse drawn vehicle for the term to carry over. But there is as much evidence that doctors used horses and buggies as well. Reviewing an 1893 issue of "The Hub" magazine. A publication specifically for the coach building tradesman, has adverts suggesting that a Phaeton, a sporty lightweight carriage was a suitable conveyance for a physician.

|

| "The Hub" in 1893 carried an advertisement for a Doctors Phaeton. |

|

| Buggy, Brougham, or Coupe? In this court record a witness isn't sure. |

Many car manufacturers claim to have a Doctors Coupe in their range: Ford, Talbot, Oldsmobile, Cadillac, Hudson for starters. There was clearly a concerted effort among car manufacturers to get doctors to purchase one of their automobiles, and they probably thought that a small, lightweight vehicle such as a coupe would be suitable for their uses.

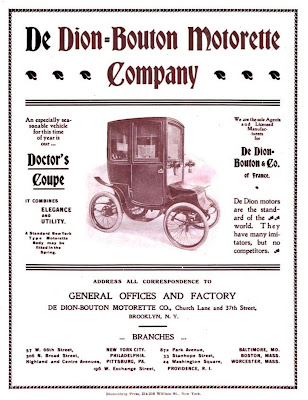

Doctors are respected members of the community and if one were to be seen in a particular vehicle. That could be good publicity for the marque. In fact, the publishers of The Horseless Age magazine printed a “Business Automobiles" special issue of their magazine in 1901 with extensive coverage of vehicles for Doctors.

|

| An advertisement for a Business Automobiles special about vehicles for Doctors. |

There is also an article in "The Hospital" magazine an English publication from 1906, less detailed than the one in the Horseless Age, that treated the reader as someone who didn't know anything at all about the new method of transport called the automobile. In that piece, three vehicle styles were recommended as suitable for the profession; the Runabout, the Brougham, and the Landaulette. Amusingly, the article also recommends that the physician should consider a coachman/chauffeur, which is probably why the Brougham and Landaulette were recommended. Landaulette is a term that has passed into obscurity now, but in the early days of the automobile, it was a larger version of the Brougham where the passengers sat in a covered or convertible section and the driver sat in the open.

Then I came across something that really grabbed my attention. The story of the first physician in the USA to use a vehicle in his practice.

That was Doctor Carlos Booth, of Youngstown Ohio. In 1895 he designed his own vehicle, and had it made by the Freedonia Carriage and Manufacturing company of Youngstown, using a Pierce Crouch engine for power.

Dr. Booth called the vehicle "The Cab" though people who saw it called it the “Milk wagon”. Capable of a top speed of 18mph it could climb a 12% grade at 4mph. Impressed with his own creation he called it "the most serviceable motor wagon as has yet been produced." He even entered it in a motor race in New York, but it broke down half way around. Two photographs of the good doctors "cab" have come to light. One with an enclosed cab and the other open topped.

|

| Doctor Booth's "cab" |

|

| This second view of Doctor Booths Cab shows it in an open topped form. |

The first mention I have found for a Doctors Coupe is in this advert from The Horseless Age in January 1900 for a DeDion-Bouton. It looks like a Model Y DeDion. But in a previous magazine advert the vehicle was described a “Doctors Brougham”.

|

| So far, the earliest reference I have found to the Doctors Coupe A DeDion-Bouton in "The Horseless Age" 1900. |

|

| Yet a month earlier, the same vehicle was described as a Doctor's Brougham |

Were DeDion the first to coin the term in relation to the automobile? I have yet to find anything earlier, and I would welcome any documented proof of earlier automotive use of the term.

Sunday, November 24, 2019

Drive Train?

|

| The Horseless Age Masthead. |

Though more of a trade magazine than the English magazine "The English Mechanic" it did share articles with its transatlantic cousin. For example, the car construction writings of Thomas Hyler White were often featured.

As it was an industry magazine, there was little emphasis placed on home builds like in the Mechanic. However, I found this image tucked away in the letters column the other day. It grabbed my attention because as well as being interested in old cars, I am a railway enthusiast too.

|

| The image that grabbed my attention. |

R H Gunnis was a clerk at First National Bank in San Diego, CA. He may also have served on the city council in some capacity at some time, and in later years he was the Manager of the San Diego clearing house association. Intriguingly, his name is also attached to a patent for a "rotating explosion engine" in the US Patent office.

Clearly, he was a remarkably creative and ingenious man. For this parade float he didn't just build the locomotive body, he also built the wagon/car that the loco runs on too!

In his letter to the editor he stated that he had also included a photograph of the running gear/wagon underneath everything. Sadly the editor lacked the foresight to publish that image. So we'll never know how everything went together.

The "wagon" was powered by a three cylinder engine. The cylinders were 4" diameter and 5" stroke giving a capacity of 188.5 cu.in. or almost three litres. There was no mention of the transmission other than each of the four wheels were chain driven. The front wheels were 33" diameter and the rears 37" and they ran on steel tyres. Top speed of 12 mph was claimed, though I expect that in the 4th July parade it only ran at the other published speed of 4mph.

In detailing the vehicles performance, Mr. Gunnis writes that the "wagon" weighed in at 2,300 lbs, the superstructure and the carriage a further 2,000. During the parade, which lasted 2 hours the train hauled a coach load of 15 people (one who apparently weighed 300lbs) A later test showed the vehicle was capable of hauling 8,500 lbs.

The locomotive body was formed from a framework of 2 x 4s that were bolted to the car and then covered with a black cloth. The stovepipe chimney was a galvanised iron pipe. The bell, sat atop the boiler came from a real locomotive, and steam dome and sand boxes to the front and rear of the bell were made from hat boxes.

I expect you're looking at the engineer in the cab and thinking that that’s Mr Gunnis proudly driving the vehicle. You'd be wrong. For the actual driving position is in the car. The drivers head would be underneath the bell. Which apparently caused problems during the parade because of the over zealous bell ringing of the engineer!

All the discomfort must have been worth it because the creation won the most original float prize in the San Diego Fourth of July parade. Then at the end of the year "The Automobile Review" magazine selected the project as the grand prize winner in its "Automotive Curiosities" competition, winning a grand prize of $5. Which doesn't sound much today, but in 2019 terms is almost $150.

Congratulations Russell Hoopes Gunnis. I raise my hat to you.

|

| I found his signature attached to some online bank documents. To me it helps to make the whole thing real. |

Sunday, November 17, 2019

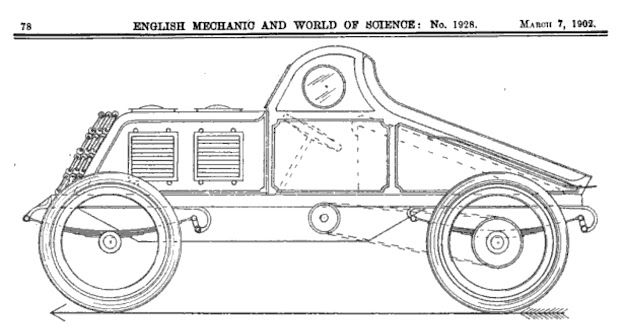

Racing cars could have been so different

For this post I delve into the pages of “The English Mechanic and World of Science” magazine again. The magazine is a rich resource of material, it’s hard to resist the temptation to visit its pages once in a while.

It is March 1902, there is no organized motor racing in England. The first proper “race” in the UK at Bexhill-on-Sea is still a few months away. It is on the mainland of Europe that road racing has taken off. Races between major cities are the rage and the famous Gordon Bennett Trophy is now well established. These races on the continent were being won by continental drivers, much to the chagrin of English Mechanic reader, and letter writer, D.W. Gawn who proposed this design of car to compete with the Europeans and win.

The car as described is certainly quite unlike anything else on the road back then, with its futuristic angular lines and streamlining. But what is really sets it apart is the driving position. The driver and mechanic lie down on their fronts on a padded, inclined couch protected on three sides and above by a cab. This brought to my mind parts of the late Sir Peter Ustinovs classic satirical recording "The Grand Prix of Gibraltar"

As the designer states in his letter to the editor. “The car would, behind the bonnet be of a wedge formation, thus reducing windage and vacuum troubles to a minimum”. He seems to know something about the concept of streamlining. The cab area would certainly offer protection from the buffeting winds the speeds would create, and if you required further protection from the elements, a canvas sheet would be drawn across the rear from the cab roof to the end of the car. He surmised that all this protection would make things more comfortable for the crew as they would not have to wear heavy coats, gloves and hats to keep them warm.

What about the pedals? How would you operate this novel vehicle? This is where things get a little vague, Mr Gawn only goes so far as to suggest that slots would be cut into the couch that the driver lies on. He considered that the area below the dashboard would be left open to the engine so that the driver and mechanic could keep an eye on things during running. Perhaps small adjustments and running repairs could be made too. This may well have resulted in quite the noisy cockpit at high speeds and high engine revs though.

As for the engine. What would power this car to victory? A four cylinder 50 HP unit is suggested in the letter. Horsepower to engine size calculations are complicated and way beyond my knowledge to work out. But a 1902 Napier Grand Prix car was said to develop 45 HP from a six and a half litre engine. I think it's fair to assume that the engine would need to be about 7 litres or 427 cubic inches at a minimum. Our designer wanted the power plant to be transversely mounted, with flywheels at each end of the crankcase, claiming that this would lead to greater stability than a similar car with a longitudinally mounted engine. Drive to the transmission, and wheels would be by chain.

The writer even says that he has shown this design to David J. Smith, supplier of parts for the English Mechanic cars. Smith was often referred to in the pages of the “English Mechanic” and was answering questions on the subject of car construction nearly every week. Clearly, he was seen as some kind of expert on the manufacture of early automobiles. Apparently Mr. Smith conceded that the idea had some merit and may well be a “goer” if a working pedal operation can be arranged, but the idea may be ahead of its time. Which in some aspects it is. The streamlined look and driving cab is like nothing else around then. But why Gawn chose to have the driver lay down on his front instead of reclining in a seat is beyond me. But this is the early days of the automobile and anything goes.

In closing, he asked for peoples opinions of the design, but I have yet to find a reply from any other readers of the magazine in the following issues.

The temptation to visualise what the vehicle may have looked like was too much for me, so I decided to dust off my iPad drawing skills and give it a go. The sketches are nothing but conjecture and a little bit of fun.

|

| The latest in racing car proposals in 1902 |

The car as described is certainly quite unlike anything else on the road back then, with its futuristic angular lines and streamlining. But what is really sets it apart is the driving position. The driver and mechanic lie down on their fronts on a padded, inclined couch protected on three sides and above by a cab. This brought to my mind parts of the late Sir Peter Ustinovs classic satirical recording "The Grand Prix of Gibraltar"

As the designer states in his letter to the editor. “The car would, behind the bonnet be of a wedge formation, thus reducing windage and vacuum troubles to a minimum”. He seems to know something about the concept of streamlining. The cab area would certainly offer protection from the buffeting winds the speeds would create, and if you required further protection from the elements, a canvas sheet would be drawn across the rear from the cab roof to the end of the car. He surmised that all this protection would make things more comfortable for the crew as they would not have to wear heavy coats, gloves and hats to keep them warm.

What about the pedals? How would you operate this novel vehicle? This is where things get a little vague, Mr Gawn only goes so far as to suggest that slots would be cut into the couch that the driver lies on. He considered that the area below the dashboard would be left open to the engine so that the driver and mechanic could keep an eye on things during running. Perhaps small adjustments and running repairs could be made too. This may well have resulted in quite the noisy cockpit at high speeds and high engine revs though.

As for the engine. What would power this car to victory? A four cylinder 50 HP unit is suggested in the letter. Horsepower to engine size calculations are complicated and way beyond my knowledge to work out. But a 1902 Napier Grand Prix car was said to develop 45 HP from a six and a half litre engine. I think it's fair to assume that the engine would need to be about 7 litres or 427 cubic inches at a minimum. Our designer wanted the power plant to be transversely mounted, with flywheels at each end of the crankcase, claiming that this would lead to greater stability than a similar car with a longitudinally mounted engine. Drive to the transmission, and wheels would be by chain.

The writer even says that he has shown this design to David J. Smith, supplier of parts for the English Mechanic cars. Smith was often referred to in the pages of the “English Mechanic” and was answering questions on the subject of car construction nearly every week. Clearly, he was seen as some kind of expert on the manufacture of early automobiles. Apparently Mr. Smith conceded that the idea had some merit and may well be a “goer” if a working pedal operation can be arranged, but the idea may be ahead of its time. Which in some aspects it is. The streamlined look and driving cab is like nothing else around then. But why Gawn chose to have the driver lay down on his front instead of reclining in a seat is beyond me. But this is the early days of the automobile and anything goes.

In closing, he asked for peoples opinions of the design, but I have yet to find a reply from any other readers of the magazine in the following issues.

The temptation to visualise what the vehicle may have looked like was too much for me, so I decided to dust off my iPad drawing skills and give it a go. The sketches are nothing but conjecture and a little bit of fun.

|

| Artists impression showing the cockpit. Complete with padded couch. |

|

| Artist’s impression of the car at speed. |

Sunday, November 10, 2019

The history of my Model T

All old cars have a history. The older they are, the more history they have. As cars get passed from owner to owner this history gets added to, sometimes the past history can get lost. Take my ‘76 MGB for example. It’s painted in the colours that a race car from Canada would have been painted in prior to 1965. (Racing green with twin white stripes.) It came with a roll cage too. The person I bought it from told me it came from Canada. But that’s all he knew. Did someone buy it with a plan to race it someday? There might well be some history there but no-one will ever know.

The history of my Model T is different. Quite a lot is known about it. The previous owner, my good friend Jan, is something of a historian, so she had had a good dig around asking questions of the previous owner.

It was through Jims Lumber business that he met Larry Menard of the Menards DIY store and motor racing family. The two must have become very good friends because we have a picture of Jim and his son stood in front of the T with Indy car driver Gary Bettenhausen who was contracted to drive for the Menards team between 1990 and 1993 so this picture can be dated to then.

1994 was a big year for Jim and the Model T. This was the year of the re-opening of the Mendota Bridge in Minneapolis. At 4,114 feet long, it was the longest concrete arch bridge in the world when it was opened in 1926. As time went on, the traffic became too much for the bridge and between 1992 and 1994 it was rebuilt to add an extra lanes of traffic.

The very earliest history, little is known about that. Even the Ford Sales records from 1926 were lost in a fire in the 1970's. So we will never be able to confirm that it was first sold in Minnesota, or that the plates the car came with are the originals. Nor will we know how many owners it had. We can only confirm five, including me.

|

| Some scrapbook photos of a Model T in need of care. Probably not my car |

What we know do know was that in the early 1950’s a 15 year old lad named Jim Meyer found an old T decaying in a barn in Minnesota and he decided that he wanted to restore it. So he bought it, and for the next however many years it travelled around the Midwest with him as he grew up and began getting on with his life

Jim was a woodworker who owned his own lumber business, and he used his woodworking skills on the restoration of the T. The wooden spokes on the wheels were all turned by hand. 48 all identical. Jim turned them from Oak, rather than the Hickory that is usually used. Perhaps the durability of the oak was preferred over the flexibility of the hickory. The spokes have lasted well over a quarter of a century.

|

| Teram Menards Indy Car driver Gary Bettenhausen with Jim and the Model T |

|

| The Mendota Bridge in 1926 |

When the bridge was re-opened there was a big celebration including a parade of civic dignitaries all in cars from 1926, the year the bridge was built. This car was in that parade. That means this car was one of the first, maybe even the first vehicle across the re-opened Mendota bridge. Reports indicate that Jim Meyer was a very proud man that day and was seen with tears in his eyes.

Sadly Jim was not a well man, and he passed away sometime after the triumphant bridge crossing.

Jims widow did not know what to do with the car, so Larry Menard offered to take it off her hands. Larry had an extensive car collection himself so for a while this car languished among a selection of Chevrolets until he decided to sell it, and that’s where my friend Jan came in.

Jan had always wanted a Model T, she had even told her father when she was younger that one day she would have a Tin Lizzie and this one came up at the right time. She was one very proud owner when we first saw the car about 15 years ago as I write this. Both my wife and I fell in love with the car when we saw it.

We told Jan that when she wanted to sell, that she should consider us. Not that I ever envisioned that happening. I always thought that it would stay in the family or that we wouldn't be able to afford it.

Jan put the car to good use as a member of the Ashland, Wisconsin Historical Society, offering rides around the town for a donation to the historical society. Many thousands of dollars were raised by this little car for historic projects in the town.

We told Jan that when she wanted to sell, that she should consider us. Not that I ever envisioned that happening. I always thought that it would stay in the family or that we wouldn't be able to afford it.

Jan put the car to good use as a member of the Ashland, Wisconsin Historical Society, offering rides around the town for a donation to the historical society. Many thousands of dollars were raised by this little car for historic projects in the town.

Then suddenly, quite out of the blue when we were in town visiting one year Jan mentioned that she was getting ready to sell and was I still interested...

Thus begins a new chapter in the history of this 1926 Ford Model T.

Thus begins a new chapter in the history of this 1926 Ford Model T.

Thursday, November 7, 2019

Further findings in Victorian automobile construction

As I researched the previous blog post reading the old issues "The English Mechanic" from the early 1900's, I could only be impressed by these Victorian and Edwardian amateur engineers or "Tyro's" as they liked to be known.

Yes, Thomas Hyler White was a professional engineer and draftsman of great skill and vision, but he and his plans helped inspire the ordinary Victorian gentleman engineer to great heights.

This person who signed his letter "FTR", for example. He describes the car he built. "I am not an engineer" he began, "nor have I an engineering workshop". His largest lathe (he must have more than one then) is only 4 1/2". He had the cylinders bored by someone else and he bought the chains, springs and the rear axle.

But it's what he did make that is amazing. The wheels are of his own manufacture. Looking at the rims in this photograph, I'm not even sure that they have tyres on them.

Then there follows a mind boggling description of his home made ignition system using a copper wire and barometer tube! This amazing vehicle could carry the builder and his family on 20 mile rides with a top speed of 10 miles per hour.

This person who signed his letter "FTR", for example. He describes the car he built. "I am not an engineer" he began, "nor have I an engineering workshop". His largest lathe (he must have more than one then) is only 4 1/2". He had the cylinders bored by someone else and he bought the chains, springs and the rear axle.

|

| FTR's Home built car |

Another remarkable contribution came from someone with the non-de-plume "Economy". He doubted that many of the magazines readers had the skills or money to construct such an elaborate vehicle as Hyler Whites first two seater. So he proposed his own design. A three wheeler inspired by the voiturettes of Léon Bollée. The Bolée brothers had finished first and second in the the very first London to Brighton car run in 1896 in vehicles of their own design. So the three wheeler concept clearly had some cachet, and would continue to do so for a few years to come. A Contal three wheeler even took part, somewhat ill-fatedly, in the 1907 Peking to Paris rally that I discussed here.

|

| The three wheeler design of Mr. "Economy" |

The design submitted by "Economy" was fairly detailed as you can see, suggesting an ash frame for the car. Wooden frames were popular because it was an easy material to work that the ordinary person would have a lot of experience with. Power came from a single cylinder air cooled engine that he thought could be manufactured from drawn steel tubing with flanges for fittings brazed on, he then goes on to describe a transmission that seems well thought out, if a little complex.

He estimates that the car would cost about 30 Victorian English pounds which in todays money is about 750 pounds or nearly 1000 US dollars. I'm not sure you could build something for that price today.

He then goes on to to invite comment on his design. Needless to say his idea for the cylinder was quickly, but politely, pooh-poohed.

In an issue dated May 24th 1901, I found this letter from David J Smith describing a version of the EM small car.

Professionally built by a company in Manchester, using the components from Smith's company, this car had a 5 1/2 HP engine and really does look most impressive. The larger, pneumatic tires and big brass headlamps help give the vehicle a whole new look compared to the version that ran on solid rubber tyres.

The Victorian era was a time of great self confidence in Great Britain and across the empire. The Victorian gentleman thought he could do anything and the content of this periodical prove that. The pages are laden with all sorts of crazy and disproved ideas for all kinds of contraptions as well as more successful inventions and theories. From small scribbles to detailed engineering drawings it was all in here.

All in all, a trawl through the Google books archive of the English Mechanic would be of interest to many a vintage car enthusiast. I'm certain I shall return to the pages of this historic publication soon.

|

| Description of the transmission |

He then goes on to to invite comment on his design. Needless to say his idea for the cylinder was quickly, but politely, pooh-poohed.

In an issue dated May 24th 1901, I found this letter from David J Smith describing a version of the EM small car.

|

| A professionally built EM car. |

|

| Compare this to the EM Car above. Same plans, many of the same parts, different execution |

All in all, a trawl through the Google books archive of the English Mechanic would be of interest to many a vintage car enthusiast. I'm certain I shall return to the pages of this historic publication soon.

Sunday, November 3, 2019

The English Mechanic.

As this is the time of that most English of motoring spectacles, the London to Brighton Run. I thought I'd reflect on a car of that era celebrated every November that fascinates me and has run in the event.

There has been several notable classic car reconstructions lately. Most notably Adrian Wards Jappic recreation and Duncan Pittaways phenomenal "Beast of Turin" So why hasn't anyone had a go at recreating this piece of motoring history?

The manufacture of a 3HP engine should be as difficult/impossible as back in 1900 but with no contemporary castings to fall back on, vintage engines of the period could be sourced. Perhaps modern CAD technology and milling techniques could make parts more easily than early 20th century forgings. Would 3D printing be possible for some parts? I do not know. I can understand the drawings but perhaps the actual building of a car might be beyond me. Perhaps more technically and mechanically minded than I could do it.

Anyone?

|

| The "English Mechanic" A special car with a place in Automotive history (Bonhams autioneers) |

The English Mechanic and World of Science (to give the publication its full title), was a weekly magazine that ran between 1865 and 1926 for the engineering and scientifically minded people of the time. It carried many constructional and engineering articles. Articles about building and improving telescopes were popular. Pieces about lathe turning and decorative woodworking shared pages with articles about gravity, photography and the building of flying machines.

In 1896 the magazine published a series of anonymous articles on how to build your own three wheeled motor carriage. Written by a gentleman called F E Blake it was little more than a detailed outline of a project compared to what was to come.

Then in January 1900 they began what is probably the most important of all their constructional series. “A small car and how to build it”. Over the next 31 weeks it described the construction of the two seat small car seen above. That makes this the worlds first Kit Car, preceding the modern "kit car" era by as much as 50 years.

Then in January 1900 they began what is probably the most important of all their constructional series. “A small car and how to build it”. Over the next 31 weeks it described the construction of the two seat small car seen above. That makes this the worlds first Kit Car, preceding the modern "kit car" era by as much as 50 years.

|

| The GA drawing of the side of the car. (Google books) |

The articles in the magazine covered everything to enable a reader to make their own version of this automobile. They included full schematic engineering drawings of the major parts of the car. Drawings that would enable a person to make the patterns to cast and make their own single cylinder three horse power engine. If that, or any other, task was beyond them, then it was possible to purchase the parts featured from an engineering company. Otherwise Benz parts were recommended, probably because Benz cars were so popular at the time. The designer was building a car himself as the articles progressed, so changes in the construction appeared as the project developed.

The two speed 3 HP engine would propel you at speeds up to 14 mph carrying two people "over any ordinary route where gradients are not abnormal" according to the then anonymous designer. The "transmission" was an interesting twin belt arrangement. It consisted of low and high speed drive belts that normally ran slack. Drive occurred when one of the belts was tightened by a pulley pressing down on it depending on the gear selected. The designer felt that a belt transmission was quieter than a friction clutch and geared transmission. There was no reverse. The relatively low powered motor was selected because it was felt that a larger more powerful unit would "give rise to unpleasant vibrations and shake the carriage to pieces very rapidly" The designer also felt that the major key to the cost was the trim and fittings, and these were left to the constructor as was the choice of solid rubber or pneumatic tyres.

The two speed 3 HP engine would propel you at speeds up to 14 mph carrying two people "over any ordinary route where gradients are not abnormal" according to the then anonymous designer. The "transmission" was an interesting twin belt arrangement. It consisted of low and high speed drive belts that normally ran slack. Drive occurred when one of the belts was tightened by a pulley pressing down on it depending on the gear selected. The designer felt that a belt transmission was quieter than a friction clutch and geared transmission. There was no reverse. The relatively low powered motor was selected because it was felt that a larger more powerful unit would "give rise to unpleasant vibrations and shake the carriage to pieces very rapidly" The designer also felt that the major key to the cost was the trim and fittings, and these were left to the constructor as was the choice of solid rubber or pneumatic tyres.

|

| GA and cross section of the cylinder, so simple I can understand it. (Google books) |

In later years, other constructional series followed, in 1901 a 1 1/2 HP motor bicycle. An article about building a steam car followed from June 1901 to March 1902 then almost immediately by a steam tricycle. The original “small car” was upgraded to a two cylinder 5-8 horsepower design in a series of articles that ran from February 1903 to 1904. Then after a few years hiatus, in 1907-1908 a small delivery van was the subject of the articles. Each car was known as an English Mechanic, there being no distinction between sizes and types.

|

| The other remaining "EM designs" The Steam car and the upgraded small car. (Internet images no copyright infringement intended) |

Today, to the best of anyone’s knowledge, only a steam car of 1901, a 1903 two cylinder car and two of the first two seater small cars have survived to this day.

All of the designs were the work of an Englishman. Thomas Hyler White, a 29 year old engineer, who began his career in the automobile industry working at Daimler between 1896 and 1898. He had also taken part in the original emancipation run in 1896. This was the event that marked the end of the notorious ‘red flag’ law and was the precursor of the world famous London to Brighton classic car run. By 1899 he had designed his own petrol engine, and was working for David J Smith & Co. This was the engineering firm that could supply the parts for these cars in the magazine if you didn’t want to make your own. To that extent you could look on these vehicle projects as marketing exercises. In addition to writing for The Mechanic magazine Hyler White also contributed articles to the American equivalent magazine "The Horseless Age".

|

| The Hyler White Petrol engine of 1899 (Graces Guide) |

Sadly, Hyler White passed away in 1920. He was only 48. He was not a well man, he suffered from consumption. He left behind a wife and two children.

I feel he is under appreciated in the history of British automobile. Though his name isn’t attached to a million selling car like the popular car makers, and it's unknown how many people actually built an English Mechanic. He certainly left his mark, and having read letters to the editor in the Mechanic magazine his designs instilled great loyalty amongst his supporters. On reflection he could be seen as important to the English car industry as people like Rolls and Royce and even WO Bentley.

As can be expected, the technology of a car built in 1900 is extremely simple. The drawings are well within the capacity of anyone who studied geometric and mechanical drawing at school to understand. I feel he is under appreciated in the history of British automobile. Though his name isn’t attached to a million selling car like the popular car makers, and it's unknown how many people actually built an English Mechanic. He certainly left his mark, and having read letters to the editor in the Mechanic magazine his designs instilled great loyalty amongst his supporters. On reflection he could be seen as important to the English car industry as people like Rolls and Royce and even WO Bentley.

There has been several notable classic car reconstructions lately. Most notably Adrian Wards Jappic recreation and Duncan Pittaways phenomenal "Beast of Turin" So why hasn't anyone had a go at recreating this piece of motoring history?

The manufacture of a 3HP engine should be as difficult/impossible as back in 1900 but with no contemporary castings to fall back on, vintage engines of the period could be sourced. Perhaps modern CAD technology and milling techniques could make parts more easily than early 20th century forgings. Would 3D printing be possible for some parts? I do not know. I can understand the drawings but perhaps the actual building of a car might be beyond me. Perhaps more technically and mechanically minded than I could do it.

Anyone?

Thursday, October 24, 2019

My home town's place in Motorsport history

|

| This panoramic view of the beach north of Mablethorpe hasn't changed since the days of the race in 1905 |

Though the draconian “red flag” act that had limited a cars speed to 4mph with a man carrying a red flag walking in front of a car had been repealed, the speeds on public roads were still limited to 14 Miles per hour and many motorists desired places to stretch the legs of their vehicles.

When, in July 1905 the Lincolnshire Automobile club (itself the first motor club in England) announced in Autocar magazine their intention to hold a race on the wonderful Mablethorpe sands, there was great interest.

Remember, that at this time, there were no motor racing circuits. Brooklands, the very first purpose built circuit, wasn’t completed until 1907. So enterprising “speed kings” had to resort to racing on private estates or, as in this case, the beach.There was to be two events, one over a flying kilometer (1,094 yards) and the other over a standing kilometer. It’s interesting to note that even at the height of the British Empire, the event was held over the “continental” kilometer distance rather than the imperial mile. The sands at Mablethorpe could certainly support the longer run.

The races were to be handicapped to give all entrants a fair chance.The Mablethorpe Amusements committee put up prizes totalling 25 guineas, Including a 10 guineas cup for each race winner. The incentives must have worked because 28 competitors entered for both of the events.

Perhaps they, and the spectators that lined the sands, were also there to rub shoulders with the famous Selwyn Francis (SF) Edge (1868-1940) He was a Lewis Hamilton of his day. Born in Australia, he came to England with his parents when he was three. He grew to be a talented sports man and businessman. He was a member of the team that won the Paris-Bordeaux cycling race in 1891 and ran a car importing and improvement business before moving on to motor racing.

By the time of the Mablethorpe event he had already won the famous Gordon Bennett trophy race and was something of a star. When he announced his intention to attempt a speed record on our sands, a huge crowd was assured, with the Great Northern Railway laying on extra trains in expectation.

|

| Edwardian Motoring hero Selwyn Francis Edge. |

Edge had been joined on the sands by his cousin Cecil, who would ride as his mechanic during record attempts, and his good friend Clifford Earp, another well known motor ace of the day. In the end the weather conditions were against the attempt and it didn’t take place. Though Mr Earp expressed an interest in coming back to attempt some records at a later date.

|

| Mr. Clifford Earp at the wheel of his Napier. |

|

| Dr. Gilpin's Richard-Brasier, is seen here easily beating Mr. Crow's Rexette which being a three wheeler got stuck in the sand. Note the huge crowd lining the entire length of the race course. |

|

| Mr. Wadsley's Orient Buckboard, leads home Mr. N. Isle's 8HP Rover. The size of crowd is amazing. |

|

| "Mablethorpe" writes to the editor of "The Motor Car Journal" |

All this history gives rise to a great what-if in English motor racing. What if SF Edge had been able to set a new speed record at Mablethorpe on that August day? Or what if Mr Earp if had come back and broke the hour record here instead of at Daytona Beach? Would people have come to the Lincolnshire coast for their attempts on Motorsport speed records? Perhaps the Mablethorpe sea front today would have memorials to those early racers on it. We can only wonder.

|

| A Daimler 30/40HP of the type driven to victory by Capt. H E Newsum |

|

| The Orient Buckboard, similar to the one driven by Mr. Wadsley. Note the tiller steering. |

Monday, October 21, 2019

Book review - The Mad Motorists by Allen Andrews

|

| An Amazing adventure |

“What needs to be proved today is that as long as a man has a car he can do anything and go anywhere. Is there anyone who will undertake to travel this summer from Peking to Paris by automobile?”

Fifty teams signed up for this great event but only five made it to the start line. This book is about this amazing, incredible adventure.

The five entrants were as follows:

An Itala driven by Prince Scipione Borghese, and his mechanic/chauffeur Ettore Guizardi. They were accompanied by Luigio Barzini from the Italian news paper Corriere della Serra.

A Dutch Spyker driven by Charles Godard with a reporter from Le Matin, Jean du Taillis.

There were two De Dion Boutons one driven by Georges Cormier with Edgard Longoni and the other Victor Collignon and Jean Bizac.

The final entrant was a Contal three wheeled cyclecar driven by Auguste Pons. With his mechanic Octave Focault.

As you read, your mind will boggle and you will stare at the page in disbelief as the adventures unfold. All the competitors wrote their own versions of the epic. Each one making themselves the heroes of the adventure, and as such, some aspects needed to be taken with a pinch of salt. Then in 1964 Allen Andrews undertook research to see if he could find out the truth, which turned into this book.

The early chapters of the book concern actually getting to the start line in China. Which itself was no mean feat. For up until a few days before the race started, the Chinese government had not even given permission for the trek to take place across their country.

Almost the next two thirds of the book are given over to the adventures getting across the Gobi desert. Once the rally started, it was found that many of the roads and tracks were too small for the Itala and the Spyker. So they actually had to be dismantled and manhandled by crews of men for a great many of the early miles. With motors being disassembled and wrapped to protect them in water crossings. Despite this the cars always started. Wether it was always first swing of the starting handle as the book suggests remains lost to history.

Before the start the entrants had made a pact to stick together until Europe for there was always strength and help in numbers. However, once into the Gobi desert things began to splinter. Borghese quickly set off at his own pace leaving the others behind, a lead he would not relinquish. Pons and Focault in their cyclecar got lost in the desert, ran out of supplies and very nearly died. Legend has it that their vehicle is still lost in the desert somewhere.

The other three did stick together for the most part, apart from a section when Godards car needed repair so badly he had to take a train ahead to effect repairs before returning to where he originally broke down and continue.

Borghese was the winner by three weeks, but to be honest he isn't the hero. Godard was. Admittedly he was a conman of a sort, making his way to the start by promising to pay with money he didn't have, even persuading car owner Jacobus Spyker to give him a car and all the spares necessary to complete the event, and he would pay him back when he got to Peking. He didn't of course, in fact he sold all the spares Spyker had given him to help raise the money for the boat ticket to Peking!

However, as the race progressed, perhaps the camaraderie between the contestants affected him, and while he could have left the De Dions in his wake when the cars reached the good roads of Europe. He didn't, they all stayed together and ran in convoy.

What really set the Godard performance aside from anything else was when his magneto failed in Siberia. In order to get it repaired he had to get on a train, travel 1500 miles to Omsk, get it repaired, return to where he had broken down. Before driving 3,500 miles almost all of it non-existent roads to meet up with his fellow competitors again. Driving 20 hour stints for 14 days to catch up. This is without one of the greatest driving feats in the history of all Motorsports.

But it doesn't end there, in his absence, Godard had been found guilty of fraud and was arrested in Berlin, so he never actually made to to the finish line. Though the motives for the charges and arrest are not as clear cut as it may seem. But to tell you everything about it would spoil the fun of reading the book.

The tale is incredible, and someone should make a film of it. All Motorsport enthusiasts, particularly rallyists, should read this book.

Thursday, October 17, 2019

Women Drivers?

Shinn has a whole series of these “foolish questions” cards, and not all were automobile related. The premise was simple, one person in the image would make a blindingly obvious remark about a situation in front of them, to be greeted with a positively surreal reply. Let’s be honest. “Operating on a Sphinx for appendicitis“? That wouldn’t be out of place in a Monty Python sketch.

The card might be seen as a very early example of the long held belief that persisted even into the 1970’s that women know nothing about cars. Though even in these earliest days of motoring there were some very accomplished female race car drivers. From Hélène van Zuylen, from France, the first woman to compete in a motor race, to the American Joan Newton Cuneo who would regularly beat the best male drivers of the day in the USA. Her racing career was put to a halt when women were banned from competing in Motorsport in the USA in 1910, allegedly because of her success.

That's one thing I love about collecting old postcards. You can be sent off on a journey of research that you never expect.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)