|

| The Horseless Age Masthead. |

Though more of a trade magazine than the English magazine "The English Mechanic" it did share articles with its transatlantic cousin. For example, the car construction writings of Thomas Hyler White were often featured.

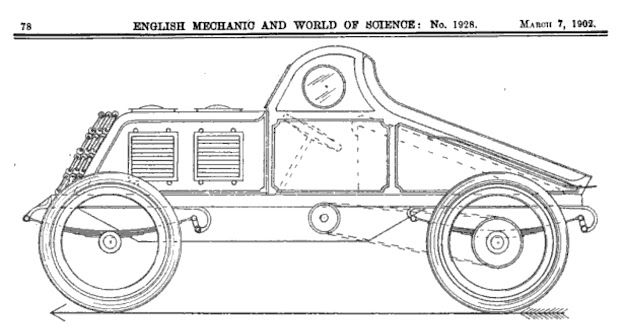

As it was an industry magazine, there was little emphasis placed on home builds like in the Mechanic. However, I found this image tucked away in the letters column the other day. It grabbed my attention because as well as being interested in old cars, I am a railway enthusiast too.

|

| The image that grabbed my attention. |

R H Gunnis was a clerk at First National Bank in San Diego, CA. He may also have served on the city council in some capacity at some time, and in later years he was the Manager of the San Diego clearing house association. Intriguingly, his name is also attached to a patent for a "rotating explosion engine" in the US Patent office.

Clearly, he was a remarkably creative and ingenious man. For this parade float he didn't just build the locomotive body, he also built the wagon/car that the loco runs on too!

In his letter to the editor he stated that he had also included a photograph of the running gear/wagon underneath everything. Sadly the editor lacked the foresight to publish that image. So we'll never know how everything went together.

The "wagon" was powered by a three cylinder engine. The cylinders were 4" diameter and 5" stroke giving a capacity of 188.5 cu.in. or almost three litres. There was no mention of the transmission other than each of the four wheels were chain driven. The front wheels were 33" diameter and the rears 37" and they ran on steel tyres. Top speed of 12 mph was claimed, though I expect that in the 4th July parade it only ran at the other published speed of 4mph.

In detailing the vehicles performance, Mr. Gunnis writes that the "wagon" weighed in at 2,300 lbs, the superstructure and the carriage a further 2,000. During the parade, which lasted 2 hours the train hauled a coach load of 15 people (one who apparently weighed 300lbs) A later test showed the vehicle was capable of hauling 8,500 lbs.

The locomotive body was formed from a framework of 2 x 4s that were bolted to the car and then covered with a black cloth. The stovepipe chimney was a galvanised iron pipe. The bell, sat atop the boiler came from a real locomotive, and steam dome and sand boxes to the front and rear of the bell were made from hat boxes.

I expect you're looking at the engineer in the cab and thinking that that’s Mr Gunnis proudly driving the vehicle. You'd be wrong. For the actual driving position is in the car. The drivers head would be underneath the bell. Which apparently caused problems during the parade because of the over zealous bell ringing of the engineer!

All the discomfort must have been worth it because the creation won the most original float prize in the San Diego Fourth of July parade. Then at the end of the year "The Automobile Review" magazine selected the project as the grand prize winner in its "Automotive Curiosities" competition, winning a grand prize of $5. Which doesn't sound much today, but in 2019 terms is almost $150.

Congratulations Russell Hoopes Gunnis. I raise my hat to you.

|

| I found his signature attached to some online bank documents. To me it helps to make the whole thing real. |